Big steps from implant advance

A new implant has allowed paralysed monkeys to walk again.

A new implant has allowed paralysed monkeys to walk again.

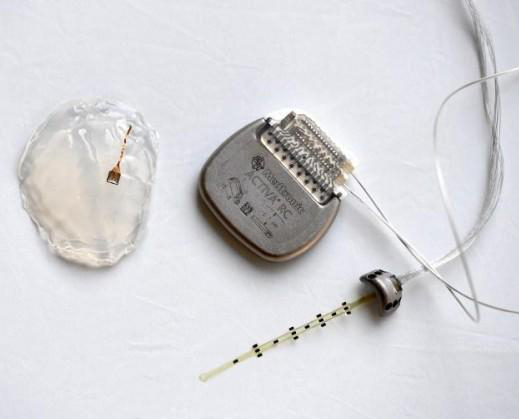

The implantable, wireless brain–spine interface uses components that have been approved for research in humans, and is a step towards clinical trials to test the efficacy of this approach in people with paraplegia.

The device includes an implant that picks up movement signals from the brain, and transmits them past the spinal injury to nodes on the part of the body that the subject could not otherwise control.

Research has already made it possible to use signals decoded from brain areas involved in planning and executing movement to control movement of a robotic or prosthetic hand.

But previous approaches had not covered the complex leg muscle activation patterns and coordination involved in walking.

Research engineer Grégoire Courtine and colleagues at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology (EPFL) developed a brain–spine interface that decodes signals from the part of the motor cortex that orchestrates leg movements to stimulate electrodes implanted in ‘hotspots’ in the lower spinal cord that modulate the flexion and extension of the leg muscles.

The authors tested the interface in two rhesus monkeys each having one leg paralysed by a partial spinal cord lesion.

One of the monkeys regained some use of its paralysed leg within the first week after injury, without training, both on a treadmill and on the ground; the other monkey took two weeks to recover to the same point.

Research Andrew Jackson suggests that, given the rapid translation of other neural interfaces from monkeys to humans in recent years, “it is not unreasonable to speculate that we could see the first clinical demonstrations of interfaces between the brain and spinal cord by the end of the decade.”

The latest paper is accessible here.

The team explains their efforts in the video below:

Print

Print