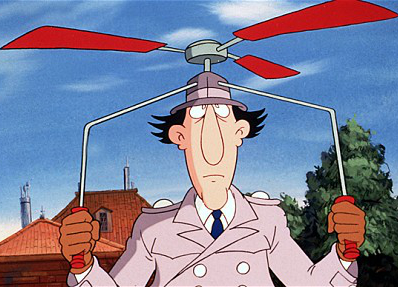

Drone laws called for in push for privacy

Some MPs say remotely piloted aircraft put public safety and privacy at risk, and there should be new laws to protect them.

Some MPs say remotely piloted aircraft put public safety and privacy at risk, and there should be new laws to protect them.

Drones are dangerous, says a House of Representatives Standing Committee on Social Policy and Legal Affairs chaired by Nationals MP George Christensen.

The committee has investigated the rise of drones in Australia, as the fun and easy-to-use flying vehicles begin to take off.

The group has released a report (PDF) which includes some suggestions for new laws to protect privacy.

There are a number of particularly good uses for drones, some of which remove safety risks from people.

Monitoring fires, mine sites, traffic, weather, forests or any number of similar activities can be more easily and safely undertaken by drones.

But this is dependent on the skills of the operator, and as the recent report found, it is an area that can be severely lacking.

Drones are readily-available and becoming widespread, but the Civil Aviation and Safety Authority (CASA) has just 110 commercial drone operators on its books.

The committee wants CASA and the Privacy Commissioner to conduct another review by 2016 to make recommendations for the future, given the rapid development of drone technology.

The government report says Australian privacy law offers only limited protection against invasive use of drones, though some state laws offer extra protection by making it illegal to use a surveillance device to watch private activities.

“The complexity of privacy laws generates considerable uncertainty as to the law's scope and effect. Evidence suggested that Australia's current privacy laws may not be sufficient to cope with the explosion of technologies that can be used to observe, record and broadcast potentially private behaviour,” the report stated.

It also said safety has now “become a prominent concern, with numerous injuries and near-misses reported across Australia”.

“The difficulty with the proliferation of these [unmanned aerial systems] … is that they are not built to any standard,” CASA’s Director of Aviation Safety, John McCormick, told the inquiry.

“There is no international standard at this stage. So their ability to maintain altitude, their ability to maintain heading, their ability to suffer equipment failure and then not crash, have not been established.”

“CASA regulations forbid recreational [drone] users from sending their craft higher than 400 feet or from flying RPAs over populous areas. They also forbid [remotely-piloted aircraft] operators from flying them within five kilometres of an aerodrome,” the report said.

There has been a lot of coverage from recent incidents where drones put public safety at risk, lending weight to the argument that there should be better licensing and safety provisions.

But they also have a long list of potentially life-saving uses, so supporters want to make sure they are not needlessly restricted.

In cases such as the following, some risks may be worthwhile (suggestion: mute the audio).

Print

Print