Techno-typing hits high speed

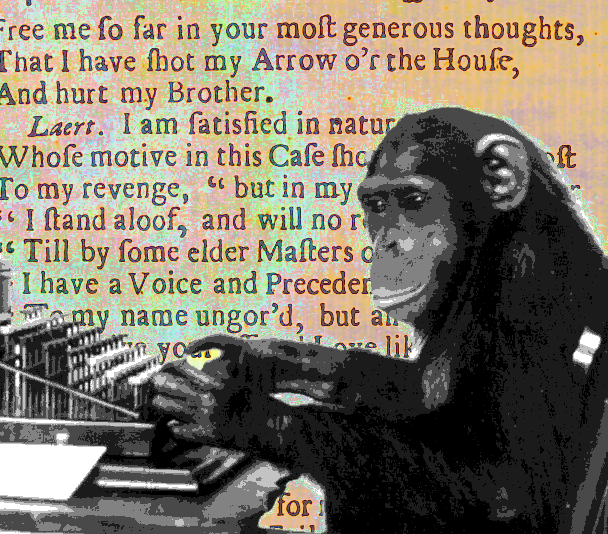

New brain-sensing technology could reduce the amount of monkeys needed to type the complete works of Shakespeare.

New brain-sensing technology could reduce the amount of monkeys needed to type the complete works of Shakespeare.

High-tech implants can directly read brain signals and use them to drive a cursor moving over a keyboard.

In a recent experiment, monkeys were able to write out passages from the New York Times and Hamlet at about 12 words per minute.

The latest iteration of the technology, developed at Stanford University, significantly improves the speed and accuracy of interpreting brain signals and moving the cursor.

“Our results demonstrate that this interface may have great promise for use in people,” said Nuyujukian.

“It enables a typing rate sufficient for a meaningful conversation.”

Other approaches to helping people type have involved tracking eye movements or the movements of individual muscles in the face, but these require a high degree of muscle control that many users find tiring, if not impossible.

Directly reading brain signals using an implanted multi-electrode array is overcoming some of these challenges.

The implants are designed to read signals from a region of the brain that usually controls hand and arm movements, like for operating a computer mouse.

The most recent breakthroughs have been in the algorithms that translate the signals and make letter selections from an alphabet grid.

“The interface we tested is exactly what a human would use,” Nuyujukian said.

“What we had never quantified before was the typing rate that could be achieved.”

The new algorithms allowed the monkeys to type more than three times faster than earlier approaches.

The monkeys involved in the tests had already been trained to type letters (with their thoughts) matching ones that appear a screen.

In the latest study they transcribed passages of the New York Times and Hamlet.

There is a significant difference between transcription and generating spontaneous writing, so researchers are keen to see how the 12 words per minute will stand up in later experiments with humans.

“What we cannot quantify is the cognitive load of figuring out what words you are trying to say,” Nuyujukian said.

“Also understand that we’re not using auto completion here like your smartphone does where it guesses your words for you.”

The recent study also provided new information on the resilience of the brain implants themselves.

The monkeys that have the implants used to test this and previous iterations of the technology were first implanted over four years ago, but the research team has found no loss of performance or side effects in the animals so far.

The team from the Brain-Machine Interface initiative of the Stanford Neurosciences Institute running a clinical trial this year with a view to testing the interface in humans.

The latest paper is accessible here, and the technology is demonstrated in the video below.

Print

Print