Face-tracking bill delayed

The erosion of human rights in Australia is being held back by a parliamentary committee.

The erosion of human rights in Australia is being held back by a parliamentary committee.

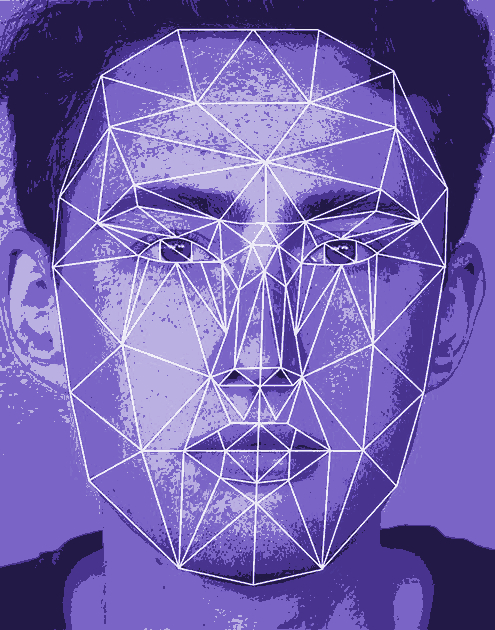

Legislation has been put forth to allow the Department of Home Affairs to administer a national facial recognition system which the Federal Government plans to share across states and territories.

The national hub would intensify governments’ citizen-tracking abilities for a range of purposes.

But the government’s parliamentary committee with the responsibility to provide oversight on intelligence and security matters, has effectively blocked the legislation – for now.

Law lecturer Dr Sarah Moulds says the proposed identity matching laws would be highly intrusive for Australians.

“Human rights groups have labelled it a massive breach of individual privacy,” Dr Moulds says.

“Under the law, facial recognition data would be shared among a wide range of agencies to confirm the identity of any Australian with government-approved documentation, such as a driver’s licence or passport, regardless of whether they are suspected of a crime.”

She believes another concern is that the software used to capture or match facial recognition, is fallible and has high error rates depending on someone’s ethnicity.

“It’s one thing to fast track border immigration controls with facial recognition technology (FRT) but relying on CCTV street cameras to accurately match faces to passports and driver’s licences is inherently risky,” Dr Moulds says.

“Using FRT in a controlled, consent-based environment like an airport or customs office to confirm identity from a passport photo is not a major concern because of the quality of the data. But relying on photos from a CCTV camera to collect information about people at a protest, or road users breaking the law for example, is problematic as it is far less reliable.”

Dr Moulds says there is a danger in assuming that facial recognition technology is 100 per cent accurate.

“When DNA testing first came in, juries were (wrongly) convinced it was infallible,” she said.

“We’re at the same stage with FRT where people believe it is accurate when in fact it has the same potential weaknesses as many other things, such as finger printing or handwriting.”

She says the rejection of the proposed Identity Matching Laws by the Parliamentary Joint Committee on Intelligence and Safety (PJCIS) should give comfort to Australians that adequate safeguards are in place to protect our privacy.

“The committee is not strictly rejecting facial recognition technology out of hand but indicating we can do better with getting the balance right.”

Dr Moulds says the COVIDSafe app is a good example of how our democratic structures can ensure this balance.

“The Federal Government initially wielded its executive powers to persuade Australians the app would be effective, and our privacy protected, but we needed that follow up parliamentary scrutiny to contest these claims,” she said.

“Unlike the US, we don’t have an enshrined Bill of Rights, nor a litigious culture, but we expect our parliament to act in our best interests and engage in open and robust debate.

“The parliament’s response to the COVIDSafe app and the proposed Identity Matching Laws show that when experts and the community more broadly engage with the parliament, it is possible to strike a better balance when it comes to the privacy impacts of these technologies.”

Print

Print